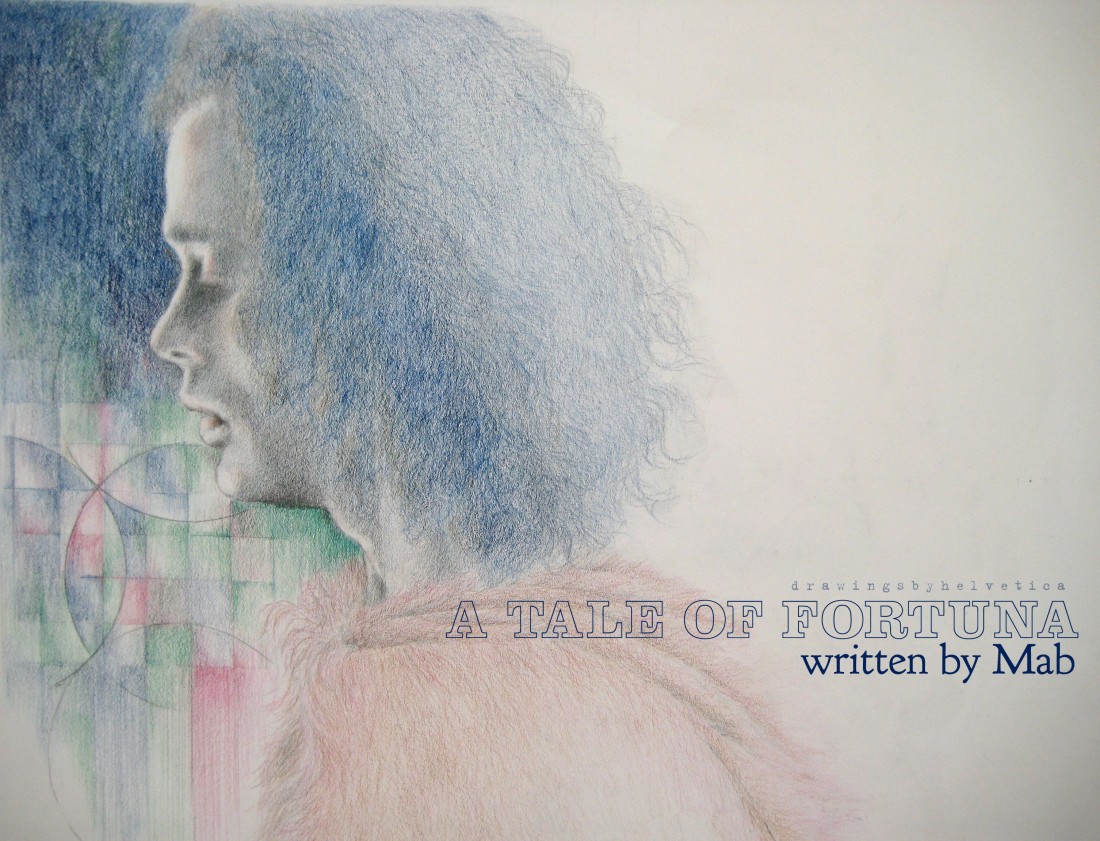

This story was written in 2009, for a fan charity auction for an animal park in California.

Summary: Jim is travelling home on furlough from his service as a knight of Fortuna when he meets a fellow knight in a tavern and finds himself drawn to the young man. It would have been only an evening’s diversion, but terrifying events at a nearby village must be investigated. This story contains sexual and violent content.

Spoilery notes and an additional picture can be found here:

There was a tiny roadside shrine sitting at the edge of the fields and when Jim saw it he said to his companions, “By your leave, gentlemen,” and dismounted his horse.

It was a rough little creche for the braided oat-straw dollies. They lay there amongst the wilted remnants of red and blue flowers that had nearly all the colour baked out of them by the last heat of late summer. Jim sank onto his knees and gently fingered the dollies, the linked loops that someone’s nimble fingers had woven, and then looked out over the stubbled fields and said, “Lady, we thank you.” The dollies were freshly made – he could still smell the last traces of the sap.

“I didn’t take you for a devotee of the Grain Mother,” Sir Arven said. Jim turned a polite face to him. It wasn’t his place to school Arven, or to embarrass Sir Thomas with the effort, not on a roadside in the northland plateau of Fortuna. It might have been a different story on campaign, though.

“I don’t profess myself her child, but she feeds us all.” Jim mounted his horse and settled into the saddle as they rode on.

“I’m a devotee of the Soldier, myself,” Arven said.

“Many fighters are,” said Thomas, trying to cut off what was likely more boasting from Arven, about the goods given to his temple by his clan, about how the Soldier’s protection gave strength to Arven’s right arm. “Thank you for paying the party’s respects, Sir James.”

Jim smiled. “It was no trouble.”

They rode on, along the narrow paved road. Jim listened with half an ear to the conversation around him. He was thinking about carrying out his errands, and he wondered how the harvest had gone at home. Not that that it was any concern of his now, not really, but the harvest size would affect the levies. He was lost in thought and calculation when he realised that Arven was talking to him again.

“And who do you profess, Sir James?”

“I profess none, but honour all.” That caused some eyebrow raising among the party, and not just from Arven. Jim didn’t care.

“Then who is your patron?” It was Thomas’s question.

“I suspect an unnamed god.”

“I see,” Arven said slyly. Jim’s jaw twitched in irritation. Arven was a man who had just enough judgement to offer no actual insult, but caused it perpetually. An unnamed god might be a great thing or a very small matter, and Arven’s tone left no doubt as to which he thought it might be.

“Enough,” Thomas said sharply. “Sir James survived Veraynya field and brought most of his troop out alive. I think that we may assume that his patron has power enough.”

Jim lifted his hand in a gesture of denial. “I’ve no wish to dissect Veraynya, or my patron.”

With Arven abashed, however briefly, conversation returned to mundane matters, and the men rode on. Jim saw Oaston first – a line of buildings and smoke haze ahead of him. Gradually, it sharpened in his sight, but it wasn’t until he could clearly see the glint of late sun on the weapons of the sentries patrolling the ramparts of the ancient fortress there that his fellow travellers began to declare that the end of the day’s journey was near, and to express hopes for the food and hospitality they hoped to find.

“What sort of man is Lord Jacobi?” Thomas asked.

“He’s reputed sensible – more a farmer than a soldier, but that’s years since, and my brother’s assessment – and my brother is all farmer.” Thomas nodded courteously, with none of the bombast that so annoyed Jim about Arven. He wondered if he should take some chance for private conversation with Thomas when they reached Oaston. Arven would be trouble somewhere, and Thomas would end with the responsibility for it.

Oaston was becoming a flourishing town, being at the crossroads for routes north and south and eastways into the Stone Sisters mountains. Jim rode through the narrow streets, dull red with the brick cobbles, surrounded by the dark blush of brick walls and tiled roofs. Their horses’ hooves clattered on the street surface, rising with a harsh echo that occasionally irritated Jim’s ears.

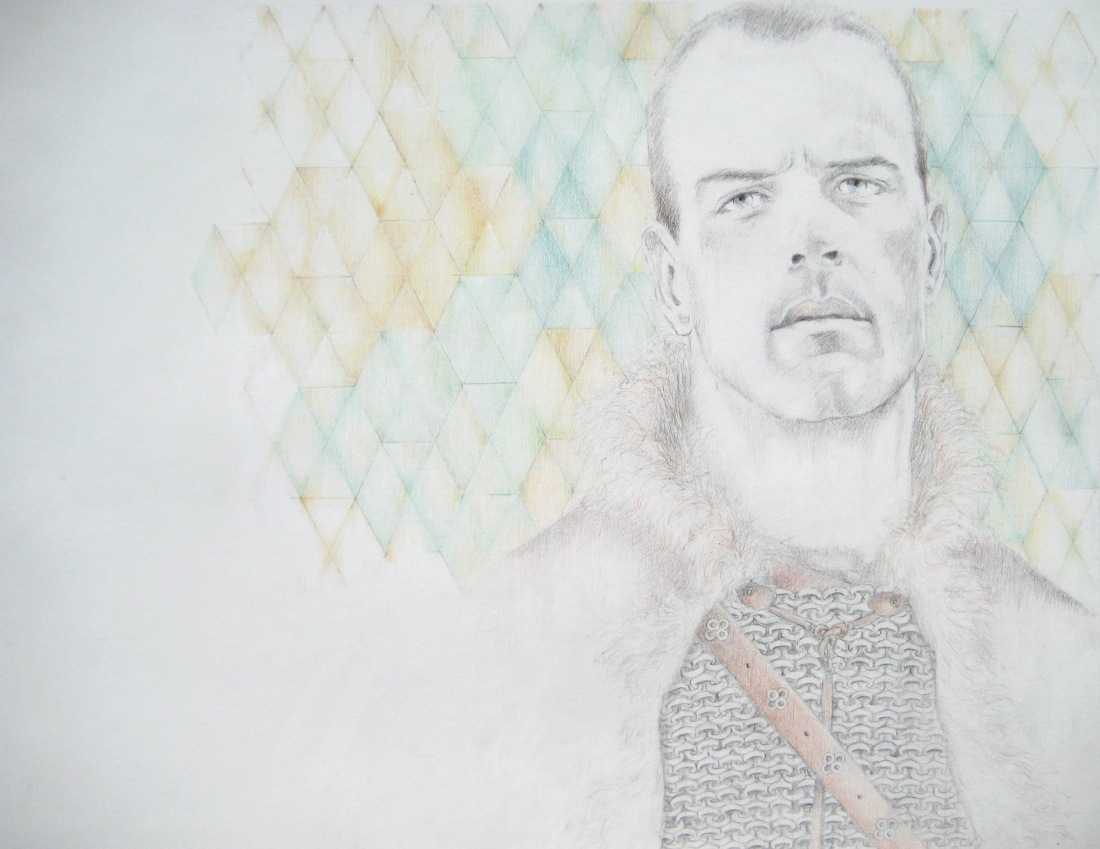

The hostel was moderately busy, and Jim inspected the stable before he surrendered his horses, warhorse and pack-horse. “There now, River, boy, there now,” he said, before handing the reins over to the groom, who appeared un-awed by River’s size. As Jim turned the corner for the hostel common room, he fingered one of the named bricks, scratched with the name of a brick maker’s ancestor. Paulus Marton, dead a hundred years now. “Let me be remembered, as I remember you,” Jim murmured, and then walked across the cobbled yard in search of something to drink, and the chance to remove the leather travelling armour that his status demanded. The room was filling and most of the benches were taken, mainly by merchants, so perhaps it was no surprise that some enterprising young man had chosen to seat himself upon the table closest the bar. He was laughing, his hands waving as he joked with the innkeeper, and Jim saw the flash of two rings upon his fingers, one of them gold.

Jim unconsciously fingered his own equestrian ring and took a closer look. The face was handsome in profile and alight with good humour. Long, curly hair was pulled back in a tail that fell down the man’s back. He was slimly built, but possessed of a broad set of shoulders under a bleached cream shirt that was decently tailored and sewn. Good boots sat on the feet that swung back and forth, as if the man couldn’t keep still. The silver ring declared him a Farseer’s Knight, which Jim supposed might excuse some eccentricities.

Jim’s despatches and letters were still in the satchel he carried; it never left him. He cast his eye over the baggage he’d left in the care of one of the boys in the hostel, satisfied that it was undisturbed. Then he approached the bar.

“What are my chances of a private room?”

The innkeeper, a skinny man with a nose too strong for his face, shrugged in apology.

“None, sir, I’m sorry. The best I can offer you is a bed to yourself, but that will cost extra.”

Jim had expected the answer but it still disappointed him. “Bath-house?” he asked.

“Five minutes walk, turning east from my door.”

Jim considered his options – food or a bath first? The bath won. “I’ll be back,” he told the innkeeper. “Don’t give that bed to anyone else.”

The bath house was tiny and so were the tubs, but everything was well-scrubbed and the water was hot. Jim asked no more. It was growing cooler when Jim stepped out into the long summer twilight and his ears were briefly cold until the last moisture of his bath dissipated. He walked briskly up the street, his nose picking up cooking smells, his eyes noting the attitude of the people he passed. Everything was as it should be here. Peace, business, respect.

When he returned to the hostel the main room was nearly empty, but there was a considerable buzz of noise from outside in the yard. Jim followed the noise to see most of the patrons and staff leaning back against the walls to leave a clear space in the middle. At opposite ends of that clear space were two men stripping off their shirts – Arven, and the young knight that Jim had seen sitting on the table swinging his legs.

Thomas was nearby, his expression sour.

“What’s going on?” Jim asked.

“A ‘friendly’ demonstration of the Farseer’s martial hands. I swear, Sir James, a formal oath to you as a good travelling companion, I’m going to do everything I can to get Arven out of my cadre. The man couldn’t guard his tongue if the Soldier himself took it between his fingers. Or if a Sister threatened to use his guts for her arrow string, which seems entirely too possible.” Thomas’s head was close to Jim’s, the words private and terse, and clearly a vent that Thomas was badly in need of. “Arven all but directly claimed that a sword was a knight’s only effective weapon, with a clear slur against any other method. Is everyone in his canton as mad?”

“I sincerely hope that Sir Arven is one of a kind,” Jim muttered back into Thomas’s ear, and was rewarded with a chuckle. “A ‘friendly’ demonstration, you said.”

“Sir Blair was certainly smiling when he made the offer.”

“Ah.”

“Indeed. I hope he’s not another blowhard like Arven. I’d like to see something puncture that idiot’s self-importance.”

Jim eyed the object of Thomas’s hopes. He stripped well, although that shouldn’t be any surprise, and moved with quick grace. Arven also displayed well enough, physically at least. The yard was loud with conversation, encouragement and catcalls, and the quiet buzz of men and women laying bets on the two contenders.

The innkeeper stepped into the middle of the yard, between Arven and Blair, and raised his hands into the air. “Esteemed patrons,” he bellowed above the din, “Sir Blair of the Farseer’s Order offers a demonstration of martial hands. If he can fell Sir Arven within five minutes, the challenge ends. If Sir Arven can remain upright or fell Sir Blair, then there will be a second bout with swords here at this time tomorrow.” He turned to Blair and said, “I hope, Sir Knight, that you won’t take offense if I hope you lose. I could sell a lot of beer tomorrow evening.” His voice had dropped, but those who were closest, and Jim, heard it and there was a roar of appreciative laughter.

Blair made a filthy gesture, to more laughter from the crowd. “Wish me better luck or I’ll send the Lord’s stewards to go through your account books with a magnifying glass,” he called back. Jim liked the voice – attractive and good-natured, of a piece with the rest of what he’d seen so far.

Both knight and innkeeper grinned broadly through this exchange, and the innkeeper cowered theatrically. “Mercy!” he declared. “Both of you give glory to your gods!” It was the formal blessing for any sporting contest. Then he stepped back into the crowd and the two knights moved forward.

Arven had been trained as a boxer, perhaps. Every knight had to learn a variety of weapons, but every fighter had his preference. They just weren’t so dogmatic in their defence of it as Arven. His stance was good. Any man who fought knew how to transfer the basic concepts between disciplines, and handling a sword built muscles that could deal a hard blow. Arven was bigger than Blair, and if he got a good grip or strike then there might well be a second challenge the next evening.

Blair was solidly knit with muscle – smaller than Arven but no less tough looking. He moved lightly and Jim could see the determination in him, for all that this was a supposedly friendly bout. Jim had seen men with broken bones and missing teeth from friendly bouts before now.

There was some dancing for position, the two men watching the other, assessing strengths, looking for weaknesses. There was a quick flurry of blows between the two of them, then another brief retreat. Jim watched all of it with a connoisseur’s eye, and some concern. Arven might be irritating but he’d paid attention to his weapons tutors. But then Blair managed a kick to the hip. Arven twisted to dissipate the worst force, but Blair clearly expected that and took his feet out from under with a move that Jim appreciated as almost beautiful in its economy and speed. Arven stumbled onto the grimy cobbles, and Blair was on him like a hunting beast, with a knee jerked into Arven’s back and his arm gripped painfully behind him.

“Acknowledge the fall, sir knight,” Blair ground out.

Arven was silent a moment, wheezing with pain and a futile effort to dislodge the victor. Finally he said, “If I must.” His voice dropped, “Sir No-Name.” He would have expected that nobody else could hear it except Blair but he hadn’t accounted for Jim’s hearing. Jim’s mouth dropped open in shock. ‘No-Name’ was deadly insult, and he waited for Blair’s next action in rigid tension.

Shadowed anger crossed Blair’s face. He looked as if he were moving to get off, but he moved awkwardly – falsely so to Jim’s eyes – and Arven screamed. Blair leaned down to him – to investigate it would have appeared to most eyes, and spoke softly, so softly that only Arven, and Jim, could possibly hear him.

“Maybe you do have your god’s protection, since he led you to say no more than the truth.” Then Blair stood and gestured to the innkeeper. “Better send for a doctor, Miles. I think I’ve dislocated his shoulder.”

If the accent hadn’t confirmed that Blair was native to this area, the familiarity with the innkeeper certainly had. Thomas, as Arven’s leader, stepped forward to help the sweating man into a more comfortable position, but the grimness in his face had a suspiciously satisfied tinge. Blair stood by, watching, and then said, “I owe you atonement, sir knight. I’ve injured your man.” His manner was genuinely contrite. Clearly he regretted the inconvenience he might have caused Thomas, if not the injury to Arven. He had no need to regret that – if Thomas made difficulties, Jim was more than ready to bear witness against Arven. Indeed, he had half-expected a far more serious challenge, rather than a guilt offering.

“We’ll talk of this tomorrow, before we move on. But for now I’d better see Arven attended to.” Thomas shrugged, and Jim repressed a smile. He suspected that Arven would be strongly encouraged into knightly fortitude once his arm was put back in place.

Blair nodded and returned to collect his belongings. The line of his back and arms as he bent to pick up his shirt gave Jim a pleasant jolt in his gut, and between that and Jim’s considerable curiosity as to why Blair hadn’t sought a far more open satisfaction of Arven, it was easy to approach the young man.

“My name is James, and I’m a Consul’s Knight. I’ve already gathered that you are Blair. That was a pretty display,” Jim said, taking the opportunity for speech as the largest group of admiring well-wishers moved off.

“Thank you. Did you have your money on me or Sir Arven?”

“I got back too late to lay any bets, but I enjoy a good show as much as anyone.” Blair was looking at him and there was an interested glint in his eye. Jim sought for some way to keep the conversation going. “You sound like a local. Do you know a reliable scribe?” So what if he’d planned to write to Simon when he arrived at The Falls?

“As it happens, yes I do, and I can show you the house.” Blair appeared amused, and Jim found that he liked how the expression looked on him. “Is now convenient? As soon as I check with Sir Thomas as to when I should meet with him.”

Jim nodded. Blair made his arrangements and then, with Jim by his side, turned east from the hostel door with a quick stride, taking Jim down the streets he’d already seen on his way to the bath house.

“I think I’ve picked up a touch of perfume of horse shit from Miles’s cobbles. Do you mind if I take a bath before we go any further? You’re welcome to join me, or else I can simply direct you on from there.” There was nothing overtly provocative about the question. Bath houses were places to socialise as well as wash. Still, Jim began to wonder, and to regret that he hadn’t arrived soon enough to procure a private room. After all, if anyone was likely to be smelling of horse shit from the hostel’s cobbles it was Arven, not Blair.

“I’ve already bathed this evening, but I’ll keep you company at least.”

The acceptance gained him a sunny smile. “Excellent.” Blair pushed back a strand of hair that had come loose from its tail. “I’m from Oaston, true enough, but you sound even more of a northern man.”

“The Falls. My family has estates there.”

“Are you retired then?”

“Fifth year furlough. So I’m returning to see my relatives and my old home, and I’m acting as a courier to justify some of the time it will take. And then I’m back to the Consulary Service for another term. I may look for a domestic post after – I’ll be forty by the end of my next service.” All very ordinary talk between knights and soldiers.

“The Consulary Service? Not the Soldier’s Order?”

“Not all fighters follow the Soldier,” Jim said pointedly.

“True,” Blair said tranquilly. “Gods, look at how the light is going. I’ll have to tip well to get proper hot water at this time of night.” He pushed open the door of the bathhouse, which was still unbarred and called out for the owner. The pair of them were accommodated, Blair with a tub of steaming water, Jim with a modest mug of small beer. Blair stripped with no obvious self-consciousness, but Jim watched him, and they both knew it.

“That’s a nasty scar,” Jim said of a puckered mark high on the inside of Blair’s left thigh. Blair got into his tub and sank back with an expression of utter pleasure that turned Jim’s thoughts once again to the possibility of finding somewhere even half private.

Blair turned his head towards Jim. “The wound wasn’t so bad, but it became infected. Nearly in the arms of my god and the remembrance of my people, but I was lucky. I have a mentor high in the Farseer’s regard, and he prayed over me. It turned matters my way.” He leaned his head back against the edge of the tub, and scraped his hair back from his forehead. His skin had a fine sheen of sweat from the water’s heat. Blair shrugged. “Scars are the price we pay, after all.”

“I have my share,” Jim said, and was warmed by another of those pleasant grins.

“I’m sure that you do.” Blair looked Jim over. “A pity that you’ve already bathed, James. We could compare.”

Jim laughed at this. “It’s a pity that the inn is so busy tonight. I could have showed you in private. Where you could call me Jim rather than James.” No doubt in his mind about his opportunities now.

“Ah,” Blair said in tones of smug satisfaction, “but we don’t need to worry about the inn. I have a small room in the scribe’s house. Her name is Stella, and she’s my foster-mother. She’ll have no objections to such a fine man as yourself in her home.”

“I will honour her hospitality.” The words were formal, but then Jim’s voice turned teasing. “And your strategic thinking.”

“Even if we hadn’t found ourselves in happy agreement I would have enjoyed a pleasant conversation with a fellow knight. No opportunities wasted.”

“As you say.” Jim leaned back against the wall and admired the view, and indulged further speculation about Arven’s insult to Blair. It was a dire insult – asking Blair about it without causing further offense was tricky.

Blair exited his bath and dressed, and led the way down the streets, nearly dark now. They came to a narrow house built between other narrow houses, and Blair opened the door and ushered Jim inside. The room was clearly an office – a large wooden desk faced the window, and there was the smell of paper and ink in the air, rising from chests and cupboards the way the smell of sap had risen from the grain dollies. The votive figures of the house stood upon the mantelpiece. There was no fire there on this summer evening, but there were two unlit candles flanking the little statues of the Man and the Woman. Between those representations of the householder’s ancestors was an eagle’s head finely carved in soapstone. A small posy of orange and white flowers sat in a mug alongside the figure of the Woman.

“Your mother follows the Farseer too? She must be proud of you.” More mystery. This modest house had never paid the dues owed for entrance to knightly rank and training.

“Foster-mother,” Blair corrected. “Yes, she is. And here she is.” A woman, thin and grey-headed entered. She was tall for a woman, slightly taller even than her foster son, who could be most politely described as being of middling height, especially next to Jim.

Blair smiled – and Jim saw the difference from the smiles he’d received. Blair’s smiles to him had been warm, but practiced. The look Blair turned on Stella was unabashedly affectionate.

“Mistress Stella,” Blair said formally, “may I present Sir James of the Consulary Service.”

Stella bowed. “Sir knight.”

“Mistress. I’m sorry to impose on you this way.”

“My house is always open, and Blair has the right to invite guests.” She smiled; no longer young, she was still a handsome woman. “Please, be welcome.”

Blair stepped forward to kiss her on the cheek. “I can always rely on you, Stella.”

“Oh, no doubt,” she said indulgently. “Do you need food?”

“Gods, yes.” Jim said nothing, but just for a moment Stella’s eyes went to his face, in entirely mutual amusement.

“Then I’d best feed you.”

It was simple meal – less meat than Jim would have seen at the inn, but tasty enough. Blair drew him out with talk of his most recent campaign, and then, stubbornly mindful of his pretext to continue in Blair’s company, Jim requested pen and paper, and had to repress a smile at Blair’s expression. But he paid Stella for the paper and ink and settled himself to work, while Blair sat on the wooden settle by the fireplace and chattered on.

“Who are you writing to?”

“A man I know,” Jim replied. There was an exasperated, snorting sound from the settle. “A Thargan lord. He’s called Simon.” Thargo was a reliable buyer of mercenary troops, and for all that Jim’s campaign in Thargo had ended with Veraynya, he had fond memories of Simon.

“What’s Thargo like?”

“There are no atlases in the Farseer’s Halls?”

“Of course.” There was even a tinge of genuine offense in Blair’s voice, but then he recognised that he was being teased, and his next words were simply curious. “But it’s not the same as hearing about it from someone who’s with you. The book can’t answer you if you want to know more.”

Jim shaped the letters of his greeting carefully. “To the most gracious lord of his people…” Simon, knowing Jim as he did, would shake his head, but Jim knew that Simon’s men (They were all men. The Thargans refused the service of the Sisters.) would expect flowery sentences as a mark of respect. Blair spoke behind him, his voice mellow with the satisfaction of a full stomach, and anticipation for later.

“Tell me about Thargo.”

So Jim wrote his letter, and told Blair about the grasslands where his troop had galloped and fought, although he said nothing of that last battle. He told Blair about the rest day by a golden beach, and how Jim wrote out his genealogy in the wet sand under a fierce blue sky, with Simon scratching out his own with a piece of driftwood about twenty feet along the beach, and the long disputation and explanations after. “They only count the father’s line in Thargo. And guard their women like prisoners.”

By then, Blair was standing behind him, his hands on Jim’s shoulders, pressing into the muscles with gentle strength. Even through his shirt, Jim could feel the warrior’s calluses on Blair’s hands. “You’re a swordsman,” Jim said, and Blair leaned down and pressed his mouth to Jim’s ear to murmur, “You could say that.” Jim grinned and shook his head.

The letter was finished. Blair had earlier sent a boy to the inn to make Jim’s explanations and advise Miles that he needn’t keep a bed for Jim, and to ask Thomas to watch Jim’s belongings. Stella had retired to her own room, wishing Blair and Jim a good night with a quietly bawdy light in her eyes.

Blair led Jim to the tiny room, which fitted a bed and chest and little more. “It looked larger when I was young,” Blair joked, and stripped off his clothes quickly, the better to help Jim with his. “Blessed gods, but you’re beautiful.”

Jim smiled at this compliment. “So are you,” he said, and lay beside Blair on the bed – which was not wide. “So, how good a ‘swordsman’ are you?”

Blair grinned broadly and lasciviously. “Let me show you.”

***

Jim lay crowded against Blair, and felt a deep melancholy. It happened that way sometimes. He met a person, someone who touched his heart in some way, but duty meant that a night’s loving was all that could be. Tomorrow, he must travel on to The Falls. But perhaps he might see Blair again on his return journey, before he received his new orders.

“Are you stationed here?” Blair had briefly mentioned that he’d been wounded on the campaign in Andbeg – which as far from Jim’s likely posting as could be. Thargo was south, Andbeg was east.

“No. This is a brief furlough. Like you, I’m due to return to my Order soon enough.”

“Then you probably won’t be here when I return in a month’s time.”

Blair sighed, his breath warm and sweet against Jim’s skin. “No.”

“A pity.”

“Yes,” Blair said softly in the dark, ” a pity.”

Jim stared up at where the ceiling would be, if the room weren’t pitch-black. He should let his curiosity remain unsatisfied. The man beside him was one night’s company and pleasure, and no more. Besides, if he wanted to know Blair’s secret Jim would have to explain something about himself that not all hearers found comfortable to know. But it was only fair.

“Farseer followers have a reputation for knowing strange things. Does your Order have anything to say about men and women who see and hear better than anyone else?” And smell, and taste, and feel, but Jim said no more.

Blair paused before he answered. “I’ve never heard of that, although I don’t doubt that it could exist.”

“I know it exists. What do you know of Veraynya?”

A gentle palm rested across the side of Jim’s face. “A bad business, betrayal.”

“I saw men who shouldn’t have been there with approaching soldiers. I saw them from a long way off, when nobody else could. And when I saw them – there were things I’d heard in passing, that were said with a fair expectation of privacy, that I hadn’t understood, but when I saw those men…” Jim swallowed. “I ordered a retreat – and nearly had a mutiny on my hands, because my men thought that I’d gone mad.”

Blair was very still. “I’m a child of the Teacher, and I can’t pretend that this isn’t fascinating. But it’s a barter, isn’t it? You heard what Arven said and now you want an explanation.”

“Even if he’d denied the insult, you still would have had the right to challenge. But you only took private vengeance. Why?”

“I shouldn’t have done even that. But I was angry.”

“With cause,” Jim said grimly. These few hours in Blair’s company… he found himself angry on Blair’s behalf in a far more personal way now. And he needed to know. He needed it.

Blair shifted and leaned up on his elbow. “If you heard what Arven said, then you heard my reply. He spoke no more than truth, and a man shouldn’t be punished for the truth.”

Jim pondered that in considerable confusion. Oliver, his cronies – they were true no-names now in the aftermath of Veraynya. Exiled, outlawed, their names excised from their family books and knightly registers, whitewashed into oblivion from the gates of their family estates and chapels. Oliver’s mother had no son. If Oliver had children, they belonged now to some other family member, would never acknowledge their descent. There was a long bas-relief along the base of the Soldier’s chief temple in Emry, hundreds of years old. One of the figures had the face defaced, the penis knocked off, and no-one now knew the name of that man, even though the names of every other man and woman on that carving were written underneath their figures. How could Blair say that he was a no-name? It was inconceivable.

“If you think any harder, your head will pop.” The tone was light, but Jim could feel the tension in the man beside him.

“You aren’t no-name. You’re a knight. You have honour here with friends and family, and I can’t understand why you’re not planning to kill Arven in challenge tomorrow.”

Blair laughed. It was a low sound, a touch nervous “He probably can’t, either, and the bad night he’ll have between that and his shoulder is all the vengeance I’ll be taking.” He took a breath, like a diver preparing to jump, and then clambered over Jim to light the candle, his hands sure despite the gloom. Blair was no less beautiful than before in the warm light, and Jim looked his fill. Tomorrow, he’d continue his travels.

Blair opened the wooden chest beside the bed. There was the scent of well oiled wood and astringent herbs, and Blair foraged amongst the chest’s contents until he brought out a small bundle of clothes. He laid them on the bed before Jim.

“What do you make of those?” he asked.

Jim unfolded the clothes. There were three items, of a size to fit a child of maybe four or five: a pair of trousers, a collarless shirt, brief smallclothes. He looked at them, unsure of what the meaning of it all was, but aware of Blair kneeling beside him with a strange, uncertain expression on his face.

“Use that piercing sight of yours and tell me what you see,” Blair said, his voice low and hard.

“A child’s clothes – good quality.” Jim turned the shirt over and stared in confusion at the device on it. It was the face of an almost troll-like little creature – orange faced, bulbously red nosed, with a broad, toothless, grinning mouth. It stood out against the blue of the tunic. Experimentally, Jim pulled the shirt between his hands and noted the way that it stretched and then regained its shape. He ran his fingers over the face of the little troll, and felt how smooth the device was in comparison to the cloth, almost oily somehow. Everything was blue in varying shades, the trousers some form of sturdy, drill cloth. The stitches were tiny and completely even. “Blue cloth like that, evenly dyed like that – whoever wore these came of a well-off family – if a strange one.”

Blair laughed again, and Jim looked at him as Blair swiped a palm across his face.

“No family at all. Nearly twenty-two years ago, now, some crofters found a little boy wandering on the moorland to east. They brought him to Oaston, to the Watch here because like you they assumed he’d somehow strayed from a good family, foreign travellers perhaps, because he didn’t speak a word of good Fortunan. But no-one ever claimed him.” Blair’s hand stroked gently across the small shirt. “So, Jim, you see how it was wrong of me to take offence at Sir Arven.”

“And you remember nothing?”

“I knew enough to tell them my name – Blair. I was lucky that I caught Stella’s fancy and that she took me in. But no, there’s not much that I remember, except for the name of this little rascal here.” Blair’s hand stroked gently at the troll-face. “Ernie.”

“A guardian spirit of some sort?” Jim hazarded. He couldn’t imagine any other reason to put such a picture against a child’s torso.

“Maybe. It was a picture of a friend. That much I remembered, but nothing that was useful. And I must admit that I find that more than a little frustrating.”

Jim neatly folded the clothes and handed them back. He had his answer, and a hundred questions in place of one. And no time to answer any of them. “Put them back and come back to bed. It’s getting cool.”

Blair put the clothes away, closed the chest, and lay back in the bed, before blowing out the candle. “You should sleep,” he said. “You have a long day’s journey ahead of you tomorrow. And you should write out everything you know about your senses, your sight and hearing and what happened at Veraynya, and send it to a knight called Johannes at the Farseer’s main House at Juniper.” Perhaps embarrassed at the distinctly assured tone of this command, Blair added hastily, “If you’d like to. But he’d find it very interesting, as would I.”

“Maybe I’ll have the time when I reach The Falls,” Jim said and fell asleep, pleasantly crowded, pondering Blair’s strange revelation.

***

Jim started awake at the sound of an urgent voice – Stella’s. “Your pardon, Sir James,” she said while shaking Blair briskly by the shoulder.

“Stella?” Blair became more aware. “What is it?”

“Guy from the Watchhouse is on his way to the citadel, but he was kind enough to come here first. Mara has come back, but alone and hurt.”

“Shit!” Blair exclaimed and stumbled out of bed, fumbling for his clothes.

“I’m going down there – but you’ll probably be there before I am.”

Blair was dragging on his trousers, nodding. Stella rushed out the door, while Jim began to put on his own clothes.

“Mara is Stella’s cousin, and in the Watch. Retired from the service of the Sisters.” Blair dropped his shirt over his head and returned to fastening his boots. “Sir Vedren and she and two more of the watch went out to one of the eastern ways villages. They’d had reports of a beast savaging the flocks.”

Jim was nearly dressed himself, and wondering at the vehemence of Blair’s voice. That he should be worried for a hurt kinswoman was natural enough, but even after this short time of noting Blair’s manner, it seemed to Jim was there was something underlying his worry, more even than the possible loss of a knight and town servitors. His clothes pulled on, but his shirt loose and unlaced, he grabbed up his satchel of papers (whatever happened, he had a responsibility for those) and literally ran after Blair. They soon overtook Stella, who was doggedly trotting through the early morning streets at a good pace for a woman who was at least twenty years older than Jim. Blair swung around to embrace her quickly before running on and shouting back at her, “I’ll tell whatever I learn.”

Perhaps five minutes of pell-mell pace saw them at the yard of the Watchgate. Oaston had come to prominence long after civil struggles in Fortuna. The walls here were no more than token, built to stop merchants avoiding duty rather than as military defence. Inside the yard of the Watchgate were three men, one of them gentling an exhausted horse. The other two gathered around a figure lying on the ground. This clearly was Stella’s cousin, Mara, a thin woman with cropped, grizzled hair. There were bloodstained bandages wrapped around her torso and as one of the men shifted, Jim realised that she was entirely missing her right arm.

“Blessed Teacher,” Blair gasped, and ran forward to kneel beside her. “I’m kin,” he muttered to the Watchman who was offering Mara water in a clay cup. “Mara, what happened?”

The smell of blood was strong. The horse, held by a young man with ginger hair and freckles, was clearly bothered by it despite its exhaustion. The woman had ridden it bareback from wherever she’d come; it looked like a farmer’s dray horse.

Mara took a few sips of the water. “Blair. The others are all dead and those poxy cowards of crofters – I told them to at least cover them and say some prayers over them but I don’t know….” Her face creased in a spasm of pain. “They’re alone up there, in pieces, without blessings…” One of the Watchmen choked at the words ‘in pieces’. Mara’s breaths were shallow, but they had the appearance of terrible effort for all the tiny movement. “It roared, had an eye like a bonfire. It drove straight through us, the horses are all gone too….” She stopped, clearly losing strength.

“We’ll tell Lord Jacobi. That’s everything?”

The woman nodded, and then shut her eyes. Jim reckoned she wasn’t far from death. There was a harsh noise in his ear – Stella, desperately out of breath, hurrying to fall on her knees before her cousin, taking heaving breaths before she gasped out, “Oh, Mara, oh sweetheart.”

“We need a cart, or a litter. Lord Jacobi has to see her.” Blair looked back at Jim.

“How far has she come?” Jim asked.

“A day’s steady ride.”

Jim shook his head. She would have lost a great deal of blood, and he suspected that the beast, monster, whatever it was that had killed outright three men and four horses hadn’t left Mara with merely a torn away arm. He doubted that the woman would wake to make any report to Lord Jacobi. Still, Blair was right. The Lord and his counsellors should at least see her.

“Blair!” Stella’s voice was rough. She sounded as if she was about to burst into tears. “You’re the only priest we have here now. Give her the Farseer’s blessing at least.”

Blair looked as if he might have disputed this, but Stella said, “Her nearest Sisters are a day away. I’m her kin, I give you the right, but don’t let her go alone.”

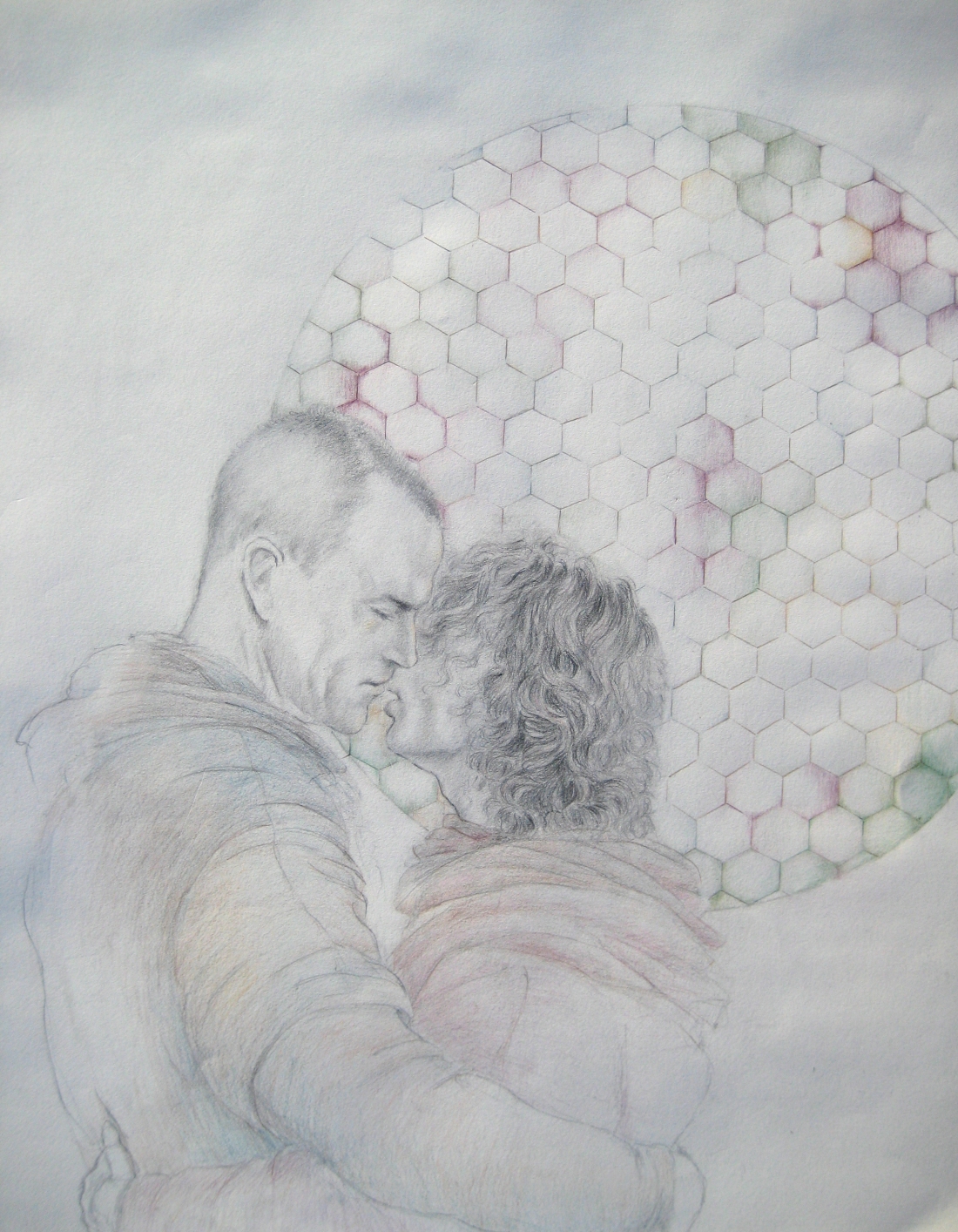

“All right. Give her to me.” Mara was shifted to lie cradled in Blair’s arms, propped with her back to his chest, her head lolling back on Blair’s shoulder. Blair lifted one hand to lie it across the side of Mara’s face. She was bruised there; it showed darkly purple against the deathly pallor, and Jim could see, could almost feel the gentleness of Blair’s touch. He began to murmur into her ear.

“Blessed Teacher. Speak to this woman’s god for me. Take Mara’s soul wherever she has been promised, let her rest with her Sisters and her loved ones.” There were tears in his eyes, and Blair kissed Mara’s temple. “Do you remember how you used to tell me stories, Mara? I do. I’ll remember you. Stella will remember you. Your Sisters will remember you, your name will be inscribed on your family gate, your body will return to our earth and you will never leave us. Farseer, you know where she’s going. Ease her way.”

There was a bell ringing in the citadel above. Jim suspected that the messenger had delivered his news – the clang was harsh and urgent. He was right about that; and he was right about Lord Jacobi’s chances of interrogating Mara about whatever had happened in the grasslands to the east. She died before he and his men set foot in the Watchgate yard.

***

It was a grim party that set forth a day later. Oaston was not over endowed with armed soldiery – it was a prosperous trading town in Fortuna’s heart; it sent soldiers out to make their way, it didn’t need them for its own defence. Lord Jacobi, faced with the possibility of a ravening monster descending upon the town or the traffic of the road rather than some moorland, had hard choices placed upon him. He left men and women, knights and soldiery, who lived within easy reach to guard their own and to send warning those who owed dues or service that they might yet be needed. The visiting knights he approached, acknowledging that he had no right over them, but judging the majority of them to have fresher memories of combat than the mainly retired men and women who held land locally.

There was Jacobi come to see the disaster for himself, accompanied by two Oaston guards. Thomas and three of his men travelled in the group, but not Arven, who had been sent on with the remainder of Thomas’s party to their destination with the news. There was Blair, who had genuflected at Jacobi’s feet in the Watchgate yard, his shirt smudged with the seepings of Mara’s rough bandages, and come dangerously close to demanding to go investigate. There was Jim, who had willingly volunteered his services, after leaving his precious papers in the care of Jacobi’s secretary with instructions to send them on soon. It was entirely the correct thing to have done in the circumstances. No-one would blame Jim for offering his services in such a situation; indeed, anyone would regard his presence in this group as an expression of knightly duty.

But Jim, watching Blair guide his horse down the rough track that was the only ‘road’ to the village of Eastmoor, was unsettlingly unsure of his motivations. He knew that Blair found him a pleasing companion. They had spent much of the ride in quiet talk; Jim hadn’t spoken so much in years, led on as he was by Blair’s curiosity and easy smile. But there was a tension in Blair, something that stiffened his back and soured his scent, and Jim noticed that it always came when Blair looked towards their destination. He sensed no such tension towards him. Blair might like him well enough, but clearly he had other matters weighing down his thoughts. Jim’s thoughts were weighted with his awareness of Blair, the pleasure that he was taking in his company, the regret that the end must still come soon, and vague guilt that someone else’s trouble had given him the opportunity to see the glint of sun against Blair’s hair.

They had departed Oaston at dawn, and brisk travel saw the party arrive in Eastmoor not long after midday. The noise of nine men on horseback and their packbeasts could be heard a good distance away and the village inhabitants were waiting for them as entered the open green that the cottages clustered around. There were perhaps forty people. No doubt they’d been gathering in and near the village for harvest festival. Standing at the front of the group was a woman, perhaps in her fifties, with a skin turned red raw by a life outdoors, and broad shoulders and knuckle-popped hands. The group sketched rough bows; heads nodded. Jacobi remained on his horse, but inclined his head graciously enough.

“You’re Eastmoor’s head?” he asked of the woman.

She stepped forward. “That’s so, my lord.”

“Then you’d best tell me what’s happened here.”

It was a short and sorry story; Eastmoor’s headwoman, Gwithen, was at least to the point. After the loss of the animals – some fifteen animals mutilated and killed, but not eaten, and the remainder scattered far and wide – Mara, Vedren and their companions had gone to stand watch. Sometime not long before midnight, Mara had knocked on Gwithen’s door, and a dreadful apparition she must have been to those people in her maimed state. Once roughly bandaged, she’d requisitioned Gwithen’s horse, and she must have pushed the poor beast mercilessly (but not as mercilessly as she’d pushed herself) to have arrived at Oaston by dawnlight.

Blair nudged his horse forward. “She asked you to give rites to the dead.”

There were some shamefaced expressions in the crowd, but Gwithen was unabashed. “They have covering and the handful of dirt.” And that was done grudgingly enough if the foot-shuffling that Jim saw was any indication.

Jacobi spoke again. “You must lead us to the place. And we’ll need labour and shovels for the burials.”

Gwithen nodded. “We’ve been gathering wood to burn the sheep anyway.” She wiped her hand across her face, bone-deep tiredness showing. “My lord – between the loss of the animals, and my horse…”

Jacobi held up a hand. “We’ll discuss the levies later. And your beast is safe and will be returned.”

Some small relief showed on Gwithen’s face. “We’re worried the land is cursed now.”

“That will be decided.”

The curse on the land was already decided amongst the villagers and farmers gathered here, Jim thought. The reluctance as Gwithen asked for men and women to accompany the armed company was nearly palpable, and seeing the downcast eyes and sullen expressions, Jacobi spared Gwithen the humiliation and picked out people himself.

“You show us the way,” Jacobi commanded Gwithen. “And those whom I’ve chosen will follow behind as soon as possible with what we need. I want my people in the earth before nightfall.”

Jim’s ears caught the mutter from amidst the crowd – “Before nightfall, or not in the earth at all. They can tax us to death and I still won’t stay there after dark” The man’s wife, he presumed, elbowed him and hissed in his ear, “I don’t blame you. So enough talking and make sure you dig fast.”

Gwithen stepped forward, her pace brisk, and the company followed her, for perhaps an hour. It was a beautiful day. Fortuna had lived up to her name and enjoyed good harvests over most of the country. Jim had passed fat flocks and sweet smelling orchards in his travels, and even in the comparatively barren moors here, he saw good trees, and wholesome looking grass. The sun beat down, making all the travellers sweat in the armour they wore, and the sky was a great shimmering bowl over their heads.

There was a line of carpa trees ahead, grown huge and twisted, and Jim winced as he saw the dots of crows in the sky beyond their shadow.

“We’re near?” he asked Gwithen.

“Not far past those trees, sir knight.”

Blair dropped his horse back to look at Jim. “And how did you know that?”

“I’ve told you I have good eyesight. The crows are feasting well. We’ll hope it’s only on the animals.”

Blair winced in his turn. “Bless the Grain Mother and the Wind Rider for the summer’s warmth – but it won’t make this task any more pleasant.”

They came close enough that the day’s gentle breeze confirmed to them all they were nearly there. A brief ride under the line of trees led them to open ground once more with a view down a gentle slope. Gwithen stopped and gestured, wordless.

All of the company had seen battle and its aftermath, but it was one thing to see and smell the shambles before them on foreign soil, and quite another to see it on Fortuna’s sweet earth. The horses had been restive all through the approach, and now at least two stamped nervously. One of Thomas’s men, a fresh-faced man called Olvus, spurred his horse down the slope with a shout and scattered the crows, who made their escape in a flurry of feathers and croaks. But there was nothing to be done about the buzz of flies or the reek of decay.

“Holy Mother’s tits,” Jacobi exclaimed under his breath.

The dead sheep lay in a rough pile, bloating in the heat. The horses were untouched except by the birds, their bodies sprawled in pathetically disgusting poses. One had its intestines spooled out upon the ground, either the result of its injuries or the work of the crows. Another lay in a backwards loop that indicated a thoroughly broken spine. There was a heaped square of cloth – blankets by the look of it, weighted with stones and branches – which Jim presumed was the remains of Sir Vedren and the two town guards.

Gwithen spoke, her voice constrained with what Jim suspected was suppressed nausea. “My lord, forgive us the lack of respect. But we didn’t know what we should do. And we were afraid.”

Jacobi dismounted his horse. “Sit down, and tell me the rest.” He and Gwithen remained under the trees. The rest of the company urged their beasts down the slope. There was a horse’s leg lying on the ground before Jim, and River, trained creature that he was, still shivered. Jim considered the scene and drove his horse back towards the trees and left him there before investigating on foot. There were branches torn from the carpa trees dotted about the ground, with the scent of decay rich under them. He shifted one with his foot, and saw underneath it a booted leg torn off at the knee. The sickly miasma that rose from it made Jim salivate, nauseated, and he turned his head aside and spat.

“You’re all right?” It was Blair.

“The smell caught me unprepared.”

Blair eyed the remains that had lain under the branches. “I was as angry as Mara at the thought of them lying here unburied – but I can’t blame the Eastmoor people now that I see this. It’s not something for farmers.”

“No.” Jim gazed about him – at the armed company, some still on their horses, some walking like Blair and Jim. The bodies of the horses were scattered about at some distance, as if thrown. Jim saw another couple of heaped branches – more human remnants that the villagers hadn’t been able to bring themselves to touch, but had at least tried to protect from the crows. “What could do this?” he asked. An eye like a bonfire, Mara had said.

“I don’t know,” Blair said. “But we will find out.”

Jim’s mouth tightened as he looked at the scene before them. “We will pray so.” A sound, back the way they had come, distracted him for a moment, and again he turned his back on the scene before him to walk back up the slope. “The villagers are coming.”

“They haven’t wasted any time. Good,” Thomas said.

Gwithen excused herself from Lord Jacobi and strode towards her neighbours. Jacobi joined Jim and Thomas to watch the procession of men and women with handcarts and bundles of wood and tools. “They’ve been speedy because they wish to be away from here before nightfall, and I cannot blame them. But we will see Vedren and Kai and Artus buried at least.”

A smelly, smoky bonfire dealt to the remnants of the beasts and the villagers dug the graves but it was the Fortuna knights who gathered the human remains together and arranged them as decently as possible. Blair had torn one of the blankets which covered the group of the dead to wrap Mara’s arm, which hung limp and forlorn in his grasp, marked with blood as well as the blue and green tattoos that the Sisters wore to show rank. Jacobi looked down at the neatly arranged corpses and shook his head, before he said to Blair, “That might have been you if you hadn’t been so annoying that I forbade you to go. Perhaps your god moved you.”

Blair frowned down at the grave, his expression thoughtful. “Perhaps he did. Who knows? I regret my manner, my lord.” The apology was glibly subservient, and Jim raised his eyes briefly, wondering at the relationship there. Blair was a Farseer knight, and Jacobi had followed the Soldier in his day if the decorations of his hall were anything to go by.

With the grave covered over, knights and villagers alike gathered in a circle about the disturbed ground.

Jacobi cleared his throat. “Gods and goddesses – bless your children who have died here, comfort your children who still live.” He crouched and rested his hands upon the loose earth. “Vedren, Kai, Artus. Mara. When your flesh is given back to the land, we will return and take your bones to your families. Rest in the arms of the Mother, and in the regard of your professed gods.” He stood, and cleared his throat again. “Powers of Fortuna – we ask your help. Let us avenge our friends and protect our people.”

There was a small pause, as if the villagers especially expected more, but then, at the realisation that Jacobi was finished a mutter of ‘let it be’ passed along the group. Such wildflowers and herbs as the season and grassy land offered were thrown onto the soil, and the villagers left with dispatch. It was coming on to dusk, and sky was just beginning to dull to the east, while to the west the clouds were turning blushy in the sunset.

“We will set camp, gentlemen, and for this night I think that we will keep watch together,” Jacobi pronounced.

There was a basket and a handcart left by the trees. Blankets, and food; some rabbits, a basket of apples and apricots. It made a meal, together with the rough rations that the knights had brought for themselves, and the night came on, while the fire that they built crackled and cast shadows and a red glow over the faces of the men gathered about it to consider how they should deal with the night’s task.

“What if it doesn’t come tonight?” Thomas asked. “Do we hunt it?”

“We can try,” offered Olvus.

“What of you, Sir James? You’ve hunted, I believe.” That was Blair, and Jim was grateful that he had the courtesy to be discreet after what Jim had told him of his senses. “I saw you marking the ground out. Did you see anything that we might follow?”

Jim shook his head. The scene that had met them had been puzzling as well as disturbing. “There were no marks on the ground that I couldn’t account for. Unless the beast can fly.”

“Soldier avert,” Olvus said.

“Whatever it is, it seems to like this spot. We will wait and see.” Jacobi sounded weary. “To your places, gentlemen, and be on your guard.”

The men left the comfort of the fire, all except two of the town’s Watch who accompanied Jacobi. They looked none too happy at their post, and Jim could understand that. Who knew whether fire might repulse or attract their prey? For the rest, they took up positions around the area in two groups of two and one of three, within earshot of shouts or the ring of weapons, and began the night’s vigil. Blair had offered to watch with Jim, and Jim took particular comfort in the idea of his company, and at the sound of Blair’s voice, low in the night air. Blair spoke with his horse and offered the mare an apple before he mounted and the two of them rode to their appointed position.

The moon was not quite at the full, but the light it cast was enough for Jim’s eyes.

“You asked if the Farseer’s children knew of men and women who could hear and see better than the usual.” Blair’s voice was pleasantly mellow, and definitely curious.

“Yes. I’d say that I see better now than you do, if you’re wondering.”

“I always wonder. The world is full of much to wonder at and about, after all.” The tones were droll, self-deprecating, but Jim could see how Blair sat alert on his mount, not so distracted at all as he might seem.

“I agree.” Jim had no more wish to be torn in pieces by some malevolent beast than the next man, but all was quiet about him and he was seized by determination that Sir Blair of the Farseer’s order shouldn’t be the only person who could ask questions.

“Why did you want to come here so badly?”

“To avenge Mara,” was the seemingly tranquil reply.

“A good answer, except that you wanted to come here before Mara’s death. I heard what Jacobi said to you over the grave.”

Blair’s features were smoothed out by the dim light and shadows cast over his face by his helmet, as smooth as his voice.

“These moors have seen odd things before. And there are kudos for men of my order who bring back news and knowledge.”

“What sort of odd things have the moors seen?” Jim knew, though, or could guess.

“Lost children in strange clothes, for a start.” Blair’s teeth flashed in a quick grin. “But my impatience ran away with me in my first request, and Lord Jacobi dismissed me.”

“I haven’t seen signs of impatience in you,” Jim said. “Although it’s a short acquaintance we’ve had.”

“Ah, but I haven’t anticipated frustration from you, Sir James.”

Jim shook his head in amusement. “A warning for me, Sir Blair.”

There was laughter in Blair’s voice. “I deal very badly with frustration.”

“And you a priest.”

“Yes, and I a priest.” Blair paused, to take another of those looks about him, to listen. Jim could have told him that there was nothing to see or hear, unless you counted the skitter of field mice in the grass and the whirr of the wings of a hunting owl. “Stella was amazed, but delighted.”

“The priests of the Farseer are forbidden children, I’ve heard.”

“Close enough. No great hardship for me. I can’t offer a family gate to stand under, or books of ancestors to copy or add to. What woman would care to take the risk of sex with me, except for some of the Sisters? They must give any children to the goddess – and that does meet both the spirit and the letter of the Farseer’s law. I enquired thoroughly about it when I was young enough to let my prick do all my thinking.”

“That young? A long time ago then.” Jim might have teased, but he felt a pang of sadness for Blair. There were ways to prevent conception, miscarry root for women who were willing to accept the risks, but babies happened. ‘No obligation except name’ was the ritual exchange at some festivals, but a child without even a name? It was as well that Blair could take pleasure in men.

They sat silently for a while, driving their horses in a slow, aimless walk back and forth across the grass. Blair urged his mare on to the top of a small rise but there was nothing to be seen beyond it except the similar dip and rise of grass greyed by the moonlight.

“A quiet night, so far,” Blair said.

Jim nodded. If he chose, he could hear whether the others spoke or were silent, whether they stood still in the night’s darkness, or patrolled their horses in tight rounds. But he didn’t choose to listen. The others deserved their privacy.

The night’s watch wore on in patches of silence and quiet talk, until Jim felt an odd prickle travel up his spine. He wheeled River around, and held up his hand at Blair’s quiet exclamation. For a few moments there was nothing, and then he heard a sound, a long, high pitched wail, like a scream, perhaps but of no creature that he’d ever heard before. It wasn’t loud but it still felt close, as if the dealer of that shrill, mournful sound must surely be nearby.

“Jim? Jim! What is it?”

“Can’t you hear that?”

“Hear what? The answer is no, obviously. No, I don’t hear anything. What do you hear?”

“A wail, a scream, far away, but it’s not…” River stamped his hooves; he’d not even twitched at the wail but now he was infected by Jim’s uncertain urgency. Jim stilled his horse, and listened hard, but the night’s silence only roared in his ears like the emptiness of a seashell. Their fellow knights hadn’t heard the noise either. He could hear them, still as on edge but bored as ever.

“The others?” Blair enquired.

“They seem calm enough,” Jim said sourly.

“But you heard something?”

“Yes!” Jim snapped. “I heard something but since clearly no-one else did, it’s little use to us.”

“Not necessarily so. Tell me exactly what you heard.”

Blair’s belief loosened Jim’s tongue enough for him to describe the noise, but there was no satisfaction to seeing Blair as confused as Jim.

“So is it here, or is it not?” Blair turned to look at Jim. “You said that you see and hear better than anyone else. What about the rest, what about your other senses? Could you scent this thing?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“What did you smell when we first came here?”

“I don’t know. Whatever you’d expect to smell at a scene like that.”

Blair’s voice was thoughtful. “What do you remember?”

Jim bowed his head, and frowned in concentration as he pictured what he saw as he rode down from the line of carpa trees. “Decay. Grass and tree sap. Bird shit.” His head lifted. “A battlefield smell – oil and metal, I mean, but – cloying, somehow. I don’t know.”

“You’re not comfortable with your gifts.” Blair’s face was puzzled, and Jim was grateful that his own face was no more than a blur against the dark to those observant eyes.

“You know the old saying. Happy the man ignored by the powers.” A man or woman too beloved by the divine had calls made upon them that disrupted an ordinary life. Jim had long been waiting to find out what his unnamed god might require, besides offending his family’s traditions by choosing the Consulary Service rather than the Soldier’s Order. But how could he have given only lip service to the Soldier? Dishonesty before a god was bad luck at best.

“Who is your god, then? You don’t wear a ring or a talisman.”

“My god is unnamed.”

“Interesting.” Blair clearly did find the information just that, damn him.

Jim felt a start of irritation. “Anticipating kudos for bringing back news and knowledge? Don’t count on it, there’s little enough I can tell you.”

“Perhaps I could tell you. Sometimes the unnamed gods are merely avatars of the old ones. I’ve studied such things. What shape does your god take?”

“A great cat, like a lion, only black and maneless.” Jim hoped that he wasn’t displeasing his god. He’d spent money on two medallions as a young man, small, but made of gold to give proper honour. Each of them was lost within a week, and Jim decided that his god must wish to remain obscure. Now, he waited on Blair’s answer, but the silence stretched out.

“What’s wrong?” Jim asked.

“Nothing.” Blair shook his head. “Nothing. But I’ve boasted and come to a fall because of it. I can’t answer you after all. But still – it’s a powerful avatar. We’ll hope that your god is watching over all of us.”

There wasn’t even the echo of that strange sound left in the air. There was only the night and the downs, and nothing more.

“We’ll pray so.”

***

Morning came without incident, and it was a frustrated, bored group of men who gradually gathered at the camp site under the carpa trees.

Jim’s armour felt heavy on him. He could very nearly see, and certainly feel, the vapour of the night’s dew melting off the metal and leather as the sun gradually warmed the air, and wondered, not for the first time, how much he took for granted in seeing that no-one else would ever observe.

The company sat around the fire, heating water in a tiny pot. Blair appeared with some pungent leaves in his hands. “I thought I recognised it earlier. Toothleaf.” Jim was more familiar with the plant when it was dried. Fresh, it was sharper in his mouth, but still pleasant enough, and he sipped at the tea out of a rough, horn cup, while conversation around him dwelt on the failure of the night’s watch.

“Whatever it is, it’s had good hunting or sport here. There are more toys for it again. Surely it will come back,” Thomas said.

“We’ll watch again tonight.” Jacobi nibbled at an apple, which he peeled of its skin with his knife. “In the daylight we’ll rest, but in shifts, half of us on guard at each time.”

“And wash,” Jim said, feeling his skin itch under the layers which covered him.

“A good idea, even without a bath house.” That was Blair, and there was a hint of memory in the look that he gave Jim, and more than a hint of a smile. “You’ll need help with your armour and so will I.” He turned to Jacobi. “With your leave, lord?”

“Rather you than me before the morning chill wears off. Take your turn but be quick.” Jacobi threw his apple core far out beyond the trees.

There was a stream, and a rough shepherd’s hut that might have fitted a man and two sheep on the other side of the killing ground. Jim crossed the grass, sparing a moment’s thought and gaze for the bare soil of the graves, and he and Blair walked upstream a few minutes to be clear of the sight and smell of the burned animal carcasses. Then they stripped as quickly as they could. Jim stood beside Blair and helped with the fastenings of his armour, a familiar ritual. Sometimes there were squires, sometimes a man of equal rank must help.

The ritual of removing armour might be familiar, but Blair was still new and unknown under his hands. The ingrained sweat and scent of armour and the clothing underneath was both the same and different for every man, and Jim blushed when he realised that he had clearly paused to sniff at Blair’s scent.

“I don’t mind.” The breastplate lay on the ground, and Blair leaned forward at the waist to shrug out of the heavy chainmail that sat beneath it, before he took off the overshirt. Then he put his hands on Jim’s shoulders to turn him to a more convenient angle. It was too reminiscent of the night they had shared, and Jim felt a sharp pang of desire.

“If not for this business, I’d be halfway to the Falls by now.”

Blair stared up at him, his eyes very blue in the full, clear morning light, before lowering his eyes to the buckle that he was working undone. “Where you could find hot water instead of a plain stream. Or a softer bed.”

“But you wouldn’t be there to share those things with me.” Gods. Jim hadn’t blurted such maudlin nonsense for a long time – not while sober at least.

“A ball-shrivelling dunking in a frigid stream. We have much to offer one another.” Blair took the weight of the breast plate while Jim shrugged it off, and tried also to shrug off the sting of the words. Blair smiled as he spoke, but it was the glib, practiced smile of the young man trying his luck, and Jim heard the edge of bitterness beneath the surface. There was maybe a sharp edge of comfort in the sarcasm, in the idea that Blair possibly shared Jim’s regret that they must go their own ways soon enough, assuming that they weren’t maimed or killed the next night. But for now the water beckoned.

Clothes followed the heavy weight of the armour, and Jim was a step or two behind Blair as they waded into the stream. They were perhaps knee-deep when Blair said, “Balls, meet water,” and dropped onto his haunches in the flow with a deep noise like a startled horse. Jim crouched and splashed water over his face and head, inhaling sharply at the shock of cold on his body.

“More awake now, are you?” Blair enquired.

“A true knight is the servitor of his god and his country, and is always alert,” Jim said unctuously. Blair hooted in derision and splashed a palm’s worth of water at him for his pomposity. No-one could let such an insult to his honour go by, and Blair received a full dunking before Jim, a broad grin on his face, swapped his grip to Blair’s arms and dragged him up again, spluttering but trying to laugh nonetheless. Blair’s laughter seemed to catch in his throat and he lifted his hand to hold it gently against Jim’s jaw for a fleeting moment. Then he disengaged himself and turned back to the shore.

“The others will think that our quarry has eaten us,” he said, wringing out his hair which was still gathered in a rough tail at the base of his neck. He was strong and beautiful where he stood, his feet planted amongst the grasses and stones of the water’s edge, and Jim admired him frankly for a few moments before taking the last steps out the water and bending to collect his own clothes.

“Our quarry…” he said, thinking back to the night’s noise. “Do you believe in sorcery?”

Blair halted briefly in the process of trying to draw breeches up over damp skin, completely unselfconscious as he considered the question.

“My teachers agree on all of two cases of it – in all the history of Fortuna and our neighbours in our libraries.” He bit his lip. “It happens – but you need a mad mortal and a mad god. And Fortuna’s gods are sane.” Blair’s hands moved briefly in some godsign or other, and then he stood to wrestle his clothing over his hips. “Do you think our beast is magic then?” He looked piercingly at Jim.

“Who knows? But I’ve never heard anything like last night’s noise before. Between its strangeness and the fact that no-one else heard it… it bothers me.”

Blair frowned, and then he looked around at the quiet land with a look as piercing as the one he’d given Jim. “It’s a mystery all right, I’ll give you that.” It was harder to believe in mystery when Jim could hear birdsong.

In a town, Jim would have preferred to put on clean clothes. Here, it wasn’t an option, but there were times when the well-used smell of cloth and armour could be comforting. Jim dressed, submitted to Blair’s help once more, and helped Blair in his turn. Olvus and one of Jacobi’s men were making their way towards the stream with the same intention of bathing, and Jim mock-saluted them as they walked back to the camp, but his attention was more caught by the rhythm of Blair’s steps on the grass.

***

Three nights of vigil; three nights of inactivity, of boredom, of frustration. It made the party members snappish as they gathered together once again to brew tea and eat some bread left the day before by Gwithen.

Jacobi rubbed his palm across his face.

“I’ve no wish to call down harm, but gods, I wish that our monster might make its appearance.

Thomas had drawn his sword and was inspecting it and its scabbard. Olvus reached into a bag and drew out oil and a rag which he passed to Thomas. The sword had no need of care, but it was something to do, as the care of the horses earlier had been. “My lord,” Thomas said, “we cannot stay much longer. One more night’s vigil and then we must make our way to the Soldier’s House at Whitehill.”

“I understand, Sir Thomas, and I appreciate your help.” Jacobi turned his gaze to Blair and to Jim. “Sir James?”

“I have some furlough left. I can stay a while longer.”

“And you are willing?”

Jim didn’t look at Blair. “Yes.”

Jacobi shook his head. “And you, Sir Blair. I’m inclined not to waste my breath with questions, because I know your answer.”

“Yes, my lord. I’ll stay here and keep watch.”

Jacobi sighed. “Should I ask the folk of Eastmoor the cost of their shepherd’s hut so that you can lodge here?” His tone grew sharp. “I appreciate your presence, Blair, but answers aren’t going to drop out of the sky for you.”

Blair’s mouth tightened. “As you say, my lord. But someone has to investigate a while longer yet. Why not me?” There was sharp impatience in Blair’s voice, and some of the others shared sideways glances. That was not how you spoke to a man of Jacobi’s rank.

Another head shake from Jacobi. There was a silence.

Blair stood. “With your leave, my lord. I might take a walk – a patrol.”

“If you wish. You do not actually answer to me, after all.”

Jim watched Blair stalk away, and then said, “With your leave, Lord Jacobi?”

Jacobi waved his hand, and Jim grabbed a hank of bread and followed after Blair. If there were more sidelong glances at that, curious and amused, – well, they guessed right enough.

Jim maintained a discreet distance behind Blair at first, his longer stride catching up until eventually the two of them found themselves wandering the grassland, taking a vague circuit around and about the land with the line of carpa trees a central bearing. They walked in silence for a while, but when Blair opened his mouth he was still dwelling on Jacobi’s words.

“Lord Jacobi sponsored me into the Farseer’s Order. That gives him some rights to comment.” He cast a quick, irritated look at Jim. ‘It does not give you the right’ was unspoken but clear.

“As you say, sir knight.” Jim’s tone was mild as milk and as patient as a good mouser waiting in a granary, and he received another irritated look. Blair spoke truly enough – one night of sex and a few days of comradeship gave Jim no rights, but he felt a responsibility for Blair, despite the friendship being of only a few days standing.

They walked a few strides more, before Blair burst out with, “That’s all you have to say, is it?”

“What do you suggest I say?” Jim said, with a reasonableness that he knew must be deeply annoying. He justified it to himself easily enough. Blair had said he had no rights, but if Blair wished to grant them with confidences then Jim suspected that his bland rationality might tempt them forth. Why it should matter to him, he couldn’t have explained.

“I know…I know that I am obsessed with what happened here, or what didn’t happen here, and I don’t really expect answers. But even if that’s so, someone has to be here, now, to deal with this, and as I said, why not me?”

Jim nodded. Someone had to be here. Why not Blair, or Jim? “Lord Jacobi chose to sponsor you? He must have had good reason, have known you well.”

Blair pushed strands of hair out of his face. “It’s a long story and yes, he took some interest in Stella’s foundling when he learned the story. He has some curiosity.” It was dismissive, as if a man without curiosity lacked a vital characteristic.

“Then I’ll presume that he knows this isn’t the first time you’ve eaten your heart out over this place, and what it means to you.”

“What this place means to me… It means nothing and that’s the problem.” Blair shook his head. “But I’m here now. He could have refused me in Oaston if he thought I shouldn’t be here, rather than bringing it up as a campfire argument. It’s not as if I’m the only one who came here for more than one reason.”

Jim kept his face still at the challenge. “Meaning?” he enquired thinly.

Blair lowered his eyes, but then he looked Jim in the face once more. “Meaning nothing. Or at least, meaning nothing more than that I’m glad to have you by my side. It happens that way sometimes – camaraderie, friendships. They grow strong quickly.” There was an odd mix of emotion on Blair’s face; irritation still, and uncertainty. Jim said nothing, but he nodded. Blair stepped out even more vigorously and then wheeled around, looking at the tranquil moors. “There’s not much more likely to make a man feel like a fool than stepping out well-armed and vigilant and meeting nothing scarier than a coney.”

Jim’s mouth quirked into a grin. “There’s a rabbit burrow.” He pointed ahead. “Perhaps our beast is hiding there.”

Blair snorted. “Still believing in magic, are you? It’s less common than some would have you believe.”

“There are plenty who do believe.” Jim studied Blair’s face, which was clear; but his body was still stiff with tension. “They tell evil stories of the Andbeg campaign.”

“It’s an evil campaign. But there are only arrows raining down from the sky, not curses.”

“I’ve asked for a transfer to Andbeg. It’s more important than Thargo. If the Andbeg border goes…they’re our friends. Let alone the risk to Fortuna herself.”

The sky above them was a delicate blue, strewn with wisps of cloud like lacework. Fortuna hadn’t seen invasion in a thousand years – she was the lucky country after all.

“And have you had any luck getting a transfer?”

Jim shook his head. “I know the Thargans and their land too well to be released. It’s a lucrative campaign.”

Blair grinned at that. “The Consulary Service will be glad of you since taxes will never have the same glamour as tithes. And at least your Thargan gold will help pay for the eastern campaign.”

“It’s a comfort to know that I can still be of service.”

Blair greeted this mild sarcasm with a look of affectionate amusement, before he stared up at the fresh morning sky. “Have you ever seen the Great Hall at the Farseer’s House in Juniper?”

“I’ve seen the buildings on the hill, but I’ve never been inside.” They paused for a moment in unspoken agreement, Blair again gazing around, Jim listening. A shared glance confirmed that all was quiet, and they resumed their pacing once more.

“There’s a stained glass window there that has blue in it this exact shade.” Blair’s hand reached for the sky as if he might like to grab a handful of that blue. “It was one of the first windows to be commissioned, fifty years ago now, and the knight, Andus, was a veteran of one of the Thargan campaigns too. It shows lions, and Thargan lords in their red turbans with their skin like the good earth, and the palace at Gomaan.” Blair’s voice was almost dreamy. “I hoped I might be sent to Thargo, too, but like you, I’ve been of use where I am.”

“The battle-shares out of Thargo are good. But I still wish I could be in Andbeg.”

Blair’s face was troubled. “You may get your chance. The easterners don’t stop coming. They’ve had some disaster or other; it’s a whole nation driving forth in search of safety. I could feel sorry for them except that I don’t want to see the Andbegs on their bellies under the easterners’ horse hooves.”

Jim remembered the bread he’d brought with him and he offered it. “Here. Eat something.”

Blair took it, and twisted a piece away, returned what was left. The bread was growing stale, and needed energetic chewing, but both men were hungry.

Blair sighed, and brushed crumbs from down his front. “I think I’ve finished sulking. Shall we go back? I suspect that I’ll find myself on the second shift for sleeping, somehow.” A broad grin lightened his face. “But that will only make me a truer knight of Fortuna. All that alertness and staying awake.”

Jim grinned himself and, a touch daringly, reached out to stroke his hand across Blair’s hair. “For sure. Let’s go back to our knightly duty. At least we can confirm that there are no secret lairs out here.”

***

Jim stood on duty – alone – and stared out over the moorland to see the cat bounding towards him. His sight permitted him to see it come from a long way away; he peered through hills and groves and copses as it approached, until finally the great beast leaped over the ridge to sit before him. Jim couldn’t move, not a muscle. It was like that in dreams sometimes, and he knew that he dreamed. The cat licked his hand and left him to stalk its way across the Eastmoor killing ground. It paused a moment on the earth of the graves, it sneezed in feline disgust at the remains of the burnt sheep and horses, and then it looked past Jim. Jim still couldn’t move, not a muscle, not even to turn his head, but he knew that he wasn’t alone any longer. A scent, familiar over the last days, and growing more familiar still, made itself known, and the cat stared at whatever it could see (Blair, it must be him because it was his scent) before it came back to Jim. It swivelled its head towards the graves and the heap of burned beasts, and growled before it turned back to Jim and leapt at him. He tensed, unable to even call out, let alone defend himself, but the creature was gone, and Jim started awake with a cry. Without thought, his hand reached to rub at his breastbone, and he realised that Jacobi was looking curiously at him.

“Bad dreams?” Jacobi asked.

Jim found himself struck silent for a moment. He swallowed and recovered some self-possession. “Not a bad dream, precisely. An odd one. I think….” Jim took a breath. “I think that I won’t return with you tomorrow as I’d intended. I should stay here.”

“To guard with Blair. This task is eating into your furlough, Sir James.” Jacobi’s voice was wary, and his gaze travelled to Blair who, still sleeping, rested under the carpa tree’s shade with the other sleepers. Jim had awakened first, startled out of sleep by his dream. He wiped a hand across his face.

“I know, my lord. But I dreamed…” He paused again, and some of the suspicion left Jacobi’s face. That Jim and Blair had allied themselves together was obvious, but at least the Oaston lord wasn’t completely assuming that Jim had an ulterior motive for his decision. Jim doubted that his troubled, wide-eyed state looked like that of a man planning the extension of a sexual liaison.

“Sir James. Have you ever had that old proverb quoted to you – ‘call not too often upon the gods, lest they call upon you’? It’s a favourite of mine. I keep my prayers short because of it.” Jacobi looked at Jim, a frown deepening the lines between his brows. “But the gods call on us even without our presumption, don’t they? Between Blair’s drive to come to this place, and your decision to stay behind…How long will you stay?”

Jim looked down towards the open grass. He didn’t turn his head towards Blair but, just as in his dream, he could smell the scent of him. “Until my furlough ends or until this business is resolved, I suppose.”

Lord Jacobi nodded. This was the last night for the group’s vigil. Nothing had happened, the moor had remained empty of noises or alarms, and Jacobi felt he could no longer stay away from the business of Oaston. Jim, regretting the need to leave, had intended to return with them. Blair had insisted that he would stay a while longer, and keep watch at least – and now Jim would do the same. He didn’t doubt the meaning of his dream. It was a long time since he’d seen his god.